A Potted History of Culinary Conspiracy

- Food Culture

The development of marmalade from its early predecessors of the Ancient World to the bittersweet English breakfast spread, now consumed across the globe, spans over 2,000 years. Its iconic status and place at the Brits’ breakfast table suggests it was an English invention. But the yellowed pages of manuscripts, port records and recipe books, the custodians of marmalades journey, tell us this is not so. Instead, they reveal marmalade’s colourful ancestral roots, etymology, and culinary lineage – much the same as our own family tree.

Forming an intricate roadmap from the great empires, they dispel many myths and tell an extraordinary tale of culinary happen-stance, colonisation and the democratisation of comestibles is unravelled. The fragrant quince pastes, exotic marmalada’s and syrupy sweetmeats document centuries of the cultural change of a civilising world. As a digestive, aphrodisiac, a luxury gift, and an after-dinner sweetmeat once only affordable by the gentry to a breakfast spread for the masses, the changing parade of ingredients, preparations, appearance and when they were partaken, mark their nationality and place in time.

In the first century AD, the Greeks produced melomeli by preserving raw quince in honey, as a digestive and to relieve stomach, liver, and kidney complaints. Unwittingly they discovered the chemical reaction between fruit acid, pectin, and natural sugars that transforms fruit into a delicious soft-jellied mass. The art of preserving, first with honey then much later with sugar, was born. The foundations of a new culinary journey and the making of marmalade, as we know it today, was to unfold.

By the fourth century, the seminal work on Roman daily agricultural life, Opus agriculturea by Palladius, notes quince being cooked in honey, reduced by half, and sprinkled with fine black pepper. Cooking the fruit and the addition of flavourings to local taste sets a new precedent that spurs innovation, regionality, and intrigue.

By the fourteenth century, the French made condoignac by cooking quince, honey, and red wine. In the fifteenth century, the English produced chardequince using their preferred ale-wort. The Portuguese made marmalada, a luxury quince paste flavoured with exotic rosewater and musk and created an opulent gift. Presented on the banquet table, these quince pastes were favourites of the aristocracy seeking to satisfy their sweet tooth. Alternatively, as a medicine, the marriage of fruit, sugar, and the chamber spices – clove, ginger, aniseed, and juniper berries – eased digestive troubles from excessive feasting and were thought to stimulate the seed. Carried in dainty comfit-boxes to their rooms, they allow the wealthy to dispel the torments of wind freely at their leisure and partake in amatory pursuits.

By the fourteenth century, the French made condoignac by cooking quince, honey, and red wine. In the fifteenth century, the English produced chardequince using their preferred ale-wort. The Portuguese made marmalada, a luxury quince paste flavoured with exotic rosewater and musk and created an opulent gift. Presented on the banquet table, these quince pastes were favourites of the aristocracy seeking to satisfy their sweet tooth. Alternatively, as a medicine, the marriage of fruit, sugar, and the chamber spices – clove, ginger, aniseed, and juniper berries – eased digestive troubles from excessive feasting and were thought to stimulate the seed. Carried in dainty comfit-boxes to their rooms, they allow the wealthy to dispel the torments of wind freely at their leisure and partake in amatory pursuits.

By the sixteenth century the English replaced honey with sugar and made Quodoniacke and Maramalet, while the Portuguese perfected their Marmalada. Within the next hundred years the quince was dethroned by pippins as the darling fruit. Then, as trade routes continued to open and the exotic became increasingly alluring, oranges where mixed with pippins in ever-increasingly quantities until the eighteenth century when pippins were finally usurped. The Seville orange has reigned as the hero fruit of traditional English marmalades ever since.

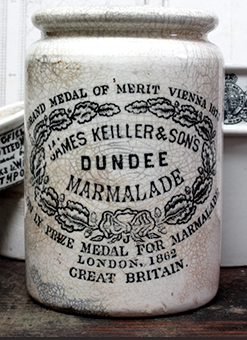

The chance purchase of a cargo of Seville oranges, in Dundee, Scotland, by James Keiller and the work of his industrious mother Jane, to make good of the bitter oranges, changed the face of marmalade and consumption patterns. The myth they invented marmalade has been disputed by many, but they did establish a marmalade factory in 1797. They aptly named their commercial product Dundee marmalade, after Marmelos, a Portuguese word for a type of quince paste similar in texture to their orange spread. The Scots were central in switching pippins with oranges and from an after-dinner treat to a breakfast spread. Using three ingredients – Seville oranges, sugar, and water – and a cooking method to specifically extract pectin from the pips, marmalades quintessential consistency of a spreadable jellied syrup with cooked peel was here to stay. No longer a firm paste, it had to be stored in pots. First in brown earthenware, then white stoneware jars, then eventually in the modern era in glass, in hermetically sealed tins and in plastic individual portion control packaging.

Until the 1700s, a bowl of ale with a floating island of toast was regarded as the most warming start to the day, that is, until the tea and toast revolution. Janet Keiller’s marmalade was the perfect consistency to spread on toast and companion to a pot of tea. The civilising of breakfast had begun. Mass production opened its availability, fuelled the new breakfast sensation, and created marmalade devotees.

Until the 1700s, a bowl of ale with a floating island of toast was regarded as the most warming start to the day, that is, until the tea and toast revolution. Janet Keiller’s marmalade was the perfect consistency to spread on toast and companion to a pot of tea. The civilising of breakfast had begun. Mass production opened its availability, fuelled the new breakfast sensation, and created marmalade devotees.

The Scots, not the English, led the way in commercial marmalade making for some time before numerous British firms opened to capitalise on the burgeoning demand. But it was the English that took it to the next level. As the British Empire expanded, marmalade was exported to the colonies as culinary comfort companions. Soon new flavours burst onto the expat’s tables based on colonial indigenous citrus varieties like lime, mandarin, tangerine, grapefruit, cumquat, and pomelo, plus a raft of inspired combinations. When returning, the expats now flaunted their new marmalade companions. Exporting new fruits back home they replaced the orange and gained widespread popularity. Recipe methods and new styles proliferated and were enthusiastically embraced.

By the 1900s there was a marmalade for everyone and occasion. Peel, finely shredded, or thick and chunky. Oranges, cooked whole and minced before adding sugar to develop a more bitter edgy flavour or sliced and soaked in water overnight to create a milder tang. Different styles emerged. Seville, bittersweet and fragrant – the marmalade benchmark. Dark Oxford, with chunky fruit peel and a full-bodied flavour from the addition of treacle. So named because it was preferred by the University Dons and students, who affectionally called it “squish”. Dundee, made in the Keiller’s Scottish style. Vintage, left to mature to create a deeper robust flavour. Californian, a light syrupy style made from sweet oranges. Even jelly marmalade, made from strained juice boiled with sugar to create a translucent base before the addition of finely shredded cooked peel.

By the 1900s there was a marmalade for everyone and occasion. Peel, finely shredded, or thick and chunky. Oranges, cooked whole and minced before adding sugar to develop a more bitter edgy flavour or sliced and soaked in water overnight to create a milder tang. Different styles emerged. Seville, bittersweet and fragrant – the marmalade benchmark. Dark Oxford, with chunky fruit peel and a full-bodied flavour from the addition of treacle. So named because it was preferred by the University Dons and students, who affectionally called it “squish”. Dundee, made in the Keiller’s Scottish style. Vintage, left to mature to create a deeper robust flavour. Californian, a light syrupy style made from sweet oranges. Even jelly marmalade, made from strained juice boiled with sugar to create a translucent base before the addition of finely shredded cooked peel.

But it didn’t stop there. An endless parade of citrus flavoured varieties and combos emerged. Dosed with whiskey or liqueurs, a soupçon of ginger, peppercorns and other spices, and citrus fruit mixtures: two-fruit, three- and even four-fruit marmalade, all progeny in the proliferating family tree.

Once a generic term for a moulded or hand-cut fruit paste, centuries of culinary exchange, continuous recipe refinement and unfettered experimentation created a unique culinary genre. Now, whatever the flavour, by definition, contemporary marmalade is a bittersweet citrus preserve with pieces of soft translucent peel suspended in it.

The final episode of marmalades journey culminated when the sugar tax reduction coincided with the development of a flourishing commercial manufacturing industry in England. By the end of the nineteenth century marmalade had established itself as the sweetheart spread and moved quickly down the social hierarchy to be consumed at all levels and in massive quantities. No breakfast table was set without it. Its sticky footprint appeared in afternoon tea fancies and was used lavishly in steamed puddings, baked custards, crumbles, and tarts. Container sizes varied to meet family and institutional demand and by the mid-1900s it was available in 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 14-pound containers. It continues to innovate and remains relevant today even as it is attacked by changing breakfast patterns and spreads.

While England has an inhospitable climate for citrus, ironically, it had become a national food and a hallmark of English cultural identity. Its cult status created marmalade aficionados including Paddington Bear, heroic explorers and of the debonair and dangerous. Paddington never left home without a secret stash of marmalade sandwiches under his hat – just in case he got hungry. Robert Scott carried a can of Frank Coopers Vintage Oxford marmalade in his 1911-12 Antarctic provisions as did Sir Edmund Hilary when he tackled Mt. Everest in 1953.

While England has an inhospitable climate for citrus, ironically, it had become a national food and a hallmark of English cultural identity. Its cult status created marmalade aficionados including Paddington Bear, heroic explorers and of the debonair and dangerous. Paddington never left home without a secret stash of marmalade sandwiches under his hat – just in case he got hungry. Robert Scott carried a can of Frank Coopers Vintage Oxford marmalade in his 1911-12 Antarctic provisions as did Sir Edmund Hilary when he tackled Mt. Everest in 1953.

The infamous fictitious James Bond, the suave audacious British Central Intelligence Officers breakfast ritual included, whole-wheat toast, Jersey butter, Frank Coopers marmalade and strong coffee. Even the British Royal Family are passionate about their marmalade. They granted Wilkin and Son, established in 1885, purveyors of the Tiptree range of preserves and marmalade, a Warrant of Appointment. Recognised as a sign of excellence, quality, and patronage by the Royal family, Wilkin and Son are entitled to display the Royal’s heraldic badge on their packaging.

Marmalade’s success is a tale of adapting to the times and medicinal and culinary practices of the day, its history intricately woven into our table arts. It’s a time-traveller moving effortlessly across geographical, cultural and time boundaries, a hospitable companion that soothed the excesses of feasting in one form and tantalised our tastebuds in another. Switching fruit, consistency, cooking methods, purpose, its moniker and when eaten, marmalade has demonstrated its resilience and ability to transform and refashion according to its cultural surrounds. It’s a culinary shapeshifter and avatar of bittersweet lusciousness and the heroine of the culinary love affair.

The melomeli, condoignac, chardequince, marmalada, and marmalet formed a continuous culinary conspiracy, sharing a common purpose – the making of the majestic marmalade. Each incarnation carrying the precious cargo of who we have been and who we are today.

TO MAKE PIPPIN MARMALET – LATER 17TH CENTURY

Take pippins & boil them for a good while, then strain it, & to a pint of that water & a little more, put a pound of sugar, then slice candied orange peels & put them into the syrup, boil it very fast, & when it is almost enough, put in some juice of the oranges & lemons, more or less according to your taste, after, boil it fast a little, and then glass it up, & if you like it you may put in s[ome am]ber [gris].

Recipe from Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery and Book of Sweetmeats, ed. K. Hess ( New York 1981). 242, No. 27, reproduced from with permission: The Book of Marmalade by C. Anne Wilson (Prospect Books, London, 1999)

REFERENCES

Ayto, J. An A-Z of Food and Drink. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 2006

Natalie Brown, “Can jam get glam?” Jams and spreads category report. January 1, 2018, https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/category-reports/can-jam-get-glam-jams-and-spreads-category-report-2018/562059.article (accessed March 23, 2021)

Bokaie, J. “Marmalade”. Marketing, June 20, 2007, 20 EBSCOhost (accessed March 23,2021)

Campion, Charles. “Preserve our Marmalade.” Daily Mail January 14, 2011https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-1346655/Preserve-marmalade-losing-sales-peanut-butter.html (accessed March 23.2021) 20, 2012).

Field, Elizabeth. “Marmalade.” The New York Times, Friday, November 2, 2012, http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/m/marmalade/index.htnl

Oddy, D.J. “Keiller’s of Dundee: The Rise of the Marmalade Dynasty, 1800-1879.” The Economic History Review, New Series 53, no.4 (2000) 8. JSTOR (accessed March 23, 2021)

“Sticky business.” Checkout, March 2009, 68. EBSCOhost (accessed March 23, 2021) December 19, 2012).

“The history of marmalade”, (https://www.dalemain.com/the-history-of-marmalade/ (accessed 22 March 2021)

Wilson, C. Anne. The Book of Marmalade: Its antecedents, its history and its role in the world today. Prospect Books, 2010.

Langley, William. “Spread the word: preserve the preserve; Omens are sour for the future of marmalade.” https://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/7175487/Marmalade-a-preserve-we-must-preserve.html 6February 2010. (accessed March 22, 2021)).

https://www.dalemain.com/the-history-of-marmalade/ (accessed April 2, 2021)